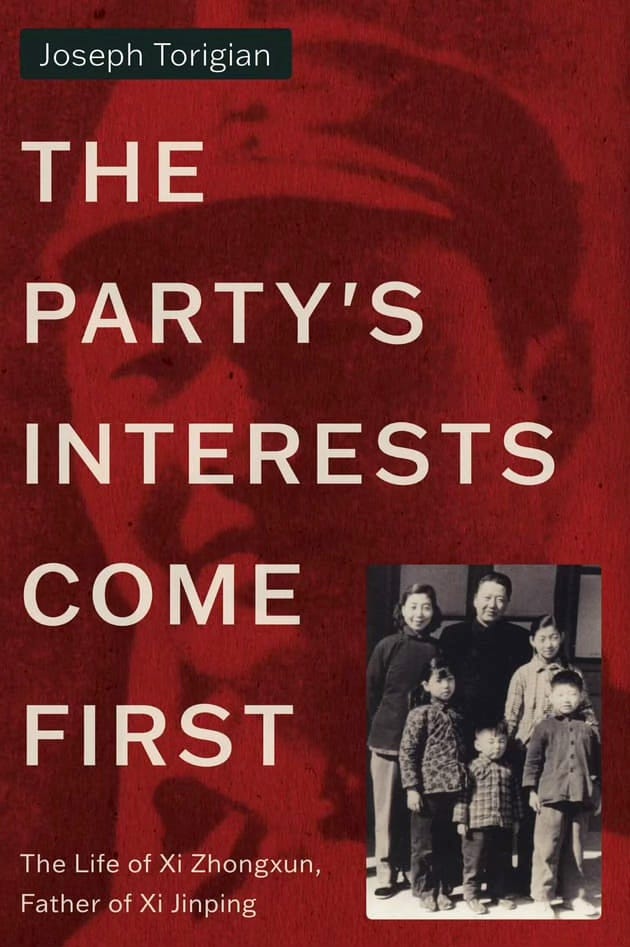

Book Review: "The Party's Interests Come First" by Joseph Torigian

A biography of Xi Zhongxun, the Father of Xi Jinping

On a chilly January morning in 1967, a senior Chinese Communist Party official named Xi Zhongxun was taken to the People’s Stadium in the eastern city of Xi’an. There he was made to bow his head low while the crowd shouted for his downfall. Taken on a truck through town to the local university, he was then subjected to hours of humiliation, forced into a “jet-plane” position with his arms twisted behind his back, and a 10 kg sign put around his neck labelling him an anti-revolutionary. The struggle session, as these performances became known, finished with a group of students rushing the stage to punch and kick him.

Xi Zhongxun had now joined hundreds of thousands of men and women as victims of China’s Cultural Revolution, often senior members of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) who had been purged by their colleagues and the student Red Guards. What happened to him was seen up and down the land, and many had it far worse, with death a not infrequent outcome of the sessions.

What makes it stand out today is that Xi was the father of Xi Jinping, the most powerful Chinese leader since Chairman Mao Zedong. Xi Jinping himself didn’t escape the Cultural Revolution, being banished to an impoverished, mountainous hamlet in 1969, when he was just 15 years old, one of millions of urban youth sent to live and work in rural villages.

Biographers of Xi Jinping refer to the impact his experience had on him during that time, starting with what happened to his father: the collapse of a man who had, until then, stood near the apex of Communist China.

The story of Xi Zhongxun’s life is told in fluid detail in an acclaimed new book by Joseph Torigian, an Associate Professor at the School of International Service at American University and a Research Fellow at the Hoover History Lab at Stanford University.

What makes this book so compelling is not just because it tells the life of Xi Jinping’s father, which makes it essential reading for anyone wanting to trace the origins of Xi Jinping’s political worldview.

Not only that, but Xi Zhongxun’s life is the story of how Communist China came into being and the half century of its rule thereafter, the People’s Republic incarnate.

Born in Shaanxi Province, at age 15 he joined the CCP in 1928, seven years after its founding. Proving himself to be a loyal and credible revolutionary, he rose through the ranks of the CCP and played an important role the Long March and the Civil War. After the founding of the People’s Republic in 1949, he held senior roles, including Vice Premier. During the Great Leap Forward, Mao’s disastrous attempt to modernise the country that led to the deaths of more than 40 million people, Xi became known for his moderate views not wholly in line with the supposed benefits Mao’s policies were achieving. He was subsequently purged in 1962 and sent into political exile. His further purging during the Cultural Revolution should have been the end of him, but he managed to rise back up the ranks under the leadership of Deng Xiaoping.

Xi played a critical part in the establishment of the special economic zones in the province of Guangdong, neighbouring Hong Kong, which in turn proved to be the springboard for the wider liberalisation of the Chinese economy. It is not an exaggeration to say that Xi was a founding father of the global economic success of China today.

It is this economic success that his son, Xi Jinping, is using as the key driver in the development of China as a, if not the great power. This is not though a book about Xi Jinping, and there are limited references to the current leader. But Torigian mentions some important asides that help the reader to dig into Jinping’s past, such as his observation that because his family had suffered so much in the Cultural Revolution, his belief that “only socialism could save China” was felt even more keenly.

What the book does well is to bring to life the challenge of living through the first fifty years of the People’s Republic. There is plenty of reference to court intrigue around Mao, and the factional struggles within the Party, and their impact on the country, are revealed in piercing detail. As Torigian relates about the fall of Hu Yaobang, the General Secretary of the CCP between 1982-87, “Hu’s fall is best understood as a product of his own shortcomings as a politician”.

“The Party’s Interests Come First” is a colossal achievement of a biography. It is incredibly well researched, with around a thousand sources listed in its bibliography and a litany of notes. But this is far more than just an academic tome. The prose flows well and Torigian makes Xi Zhongxun’s important but complex and nuanced life highly accessible. This will be a biography referenced for many years to come.

Many thanks for reading. I’ll be back next time with a new podcast.

Sam