China’s Lab‑Grown Brains Connected to AI Chips

How brain-on-a-chip systems give China a potential advantage in the race for AI supremacy

Hello and welcome back to States of Play.

It sounds like pure science fiction, but China has unveiled a startling frontier in artificial intelligence: lab‑grown human brains attached to neural interface chips.

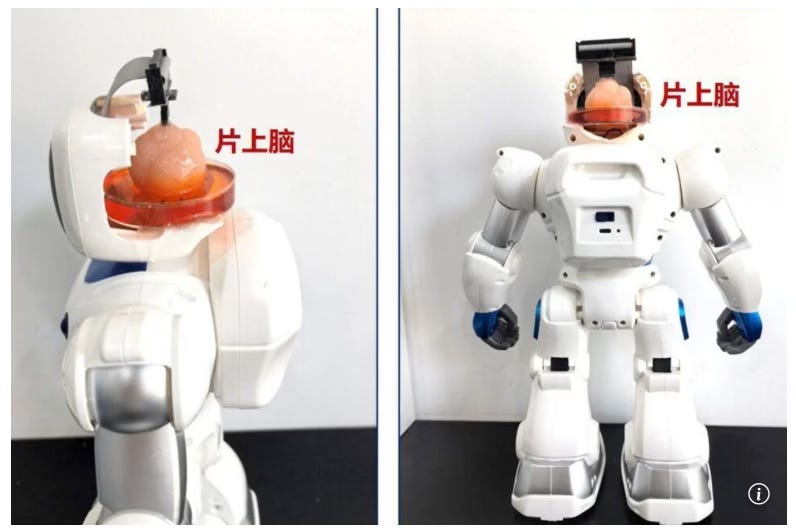

Developed by researchers at Tianjin University and the Southern University of Science and Technology, this “brain‑on‑chip” system involves growing human stem-cell derived brains (or more precisely, brain organoids) in petri dishes and then embedding this tissue into a microelectronic interface.

So far, the only published use of this perturbing development is powering robots; specifically, enabling the robot to grasp objects and autonomously avoid obstacles via feedback loops of encoded brain signals.

But these hybrid constructs - sometimes called organoid intelligence, or more graphically “wetware” - promise radically new capabilities. A robot powered by a living brain organoid can learn adaptively, drawing on the biological plasticity of human tissue combined with artificial intelligence. This could mark the first step along the path toward “biocomputers”, which could be more powerful than traditional computers.

The energy efficiency advantage is marked too: biological systems consume far less than conventional silicon chips for comparable tasks. Moreover, the system processes real‑time sensor data via biological encoding and decoding far more flexibly than fixed code could.

From American genesis to Chinese realisation

The conceptual groundwork for organoid computing emerged initially in the United States. Indiana University researchers experimented with “Brainoware” architecture, connecting brain organoids to AI tools in late 2023, demonstrating rudimentary pattern recognition and reservoir computing behaviour.

Yet these pioneers were constrained by ethical frameworks, including concerns over consenting donors, potential sentience, restrictions on duration of cultivation and more rigorous oversight. This consequently limited the scope of investigations into learning behaviour or robotic control integration.

China, by contrast, has moved more boldly, arguably because its regulatory and ethical environment permits more experimental latitude. The Tianjin work has openly embraced organoid growth integrated with robotic platforms, emphasising open‑source systems and military‑civil fusion goals under its broader China Brain Project launched in 2016. The Chinese authorities seem willing to prioritise innovation over stricter bioethical constraints accepted in the West.

Military and robotic command implications

What are the potential dividends of a living brain+chip interface?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to States of Play by Sam Olsen to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.