Sovereigntists vs Globalists: The Battle Redrawing the West

Trump, globalisation, and the backlash reshaping Western politics

Hello and welcome back to States of Play, the newsletter and podcast exploring how the world is changing, from geopolitics to technologies, from defence to demographics.

This is the first of two essays developing that argument further. For most of the post-war era, political debate was mapped along the familiar left–right spectrum: state versus market, social protection versus economic liberalism. But that axis no longer captures the battles tearing through Western societies. From Paris to Berlin, London to Washington, the struggle now centres on who decides - the nation-state or supranational bodies.

What began as a cultural divide over immigration and identity has hardened into a constitutional one, reshaping parties, alliances, and ultimately the future of the Western-led order. Next week, in the second essay, I will turn to why this matters for the global stage - and how the West’s domestic fracture threatens the survival of the order it created.

Many thanks for reading. I’ll be back soon with the second essay, and other insights into the changing world order.

Sam

A New Divide in Western Politics

At the United Nations last month, Donald Trump declared that sovereignty - the primacy of borders and national control - was the only safeguard against disorder. He mocked the UN as a failed club and promised America would act unilaterally to defend its interests. That line captured a new fracture running through the West: sovereigntists versus globalists.

For most of the post-war era, Western politics was mapped along the familiar axis of left versus right, often characterised as labour and redistribution against capital and markets. That spectrum still exists, but it no longer explains the battles now tearing at Western societies.

Across Europe, sovereigntist voices are rising. Marine Le Pen in France, the Alternative für Deutschland in Germany, Geert Wilders’ PVV in the Netherlands - all variants of the same theme. International institutions, open borders, climate treaties were once seen as guarantees of order; they are now cast as threats to national survival.

Many of these parties started as a rejection of multiculturalism and immigration. But What began as a cultural divide has hardened into a constitutional struggle. It is no longer just about attitudes to identity, belonging, or change, but about the deeper question of authority: who decides - the nation-state or supranational institutions?

This matters because the cleavage runs not just within countries but across alliances. It divides NATO, the European Union, and the transatlantic partnership at the very moment China is offering the world a rival vision: a model of multilateralism, “sovereign equality” for the Global South, and promises of development. Fragmented at home and incoherent abroad, the West risks not just domestic gridlock but the loss of its claim to global leadership.

From Somewheres and Anywheres to Sovereigntists and Globalists

In The Road to Somewhere (2017), published just after the Brexit vote, David Goodhart described two enduring groups. Somewheres are rooted in place, family, and tradition, deriving identity from belonging and wary of rapid change. Anywheres are educated, mobile, and cosmopolitan, building identity on achievement and seeing the world as open and borderless.

Brexit was the purest expression of this divide: Somewheres voted Leave, Anywheres Remain. The question was not just trade rules but belonging and control - borders, law, and culture on one side, integration and mobility on the other.

But identity is only half the story. The cleavage is also constitutional: about where authority lies.

Sovereigntists argue that ultimate authority must rest with the nation-state. Laws, migration policies, trade rules, even climate targets should be decided domestically, not ceded to Brussels or New York. Their question is who decides?

Globalists argue that national borders cannot contain modern problems. Trade, finance, migration, pandemics, and climate change all demand supranational cooperation. Their question is how do we solve what no state can fix alone?

The overlap with Goodhart’s Somewheres and Anywheres is strong but imperfect. What has emerged is a sharper divide - not just about cultural outlooks, but about authority, legitimacy, and the future of democracy itself. And as the past two decades have shown, nothing has turned theory into grievance more powerfully than globalisation.

Sovereigntism is Not Nationalism

The new cleavage is often caricatured as a revival of nationalism. That is a mistake. Sovereigntism is not nationalism.They often overlap, but they are distinct doctrines.

Sovereigntism is constitutional. It is about authority. Who has the right to decide? For sovereigntists, the answer must always be the nation-state. Laws, trade rules, migration policy, climate targets - these should be decided domestically, not ceded to Brussels, Geneva, or New York. The central question is who decides?

Nationalism, by contrast, is cultural. It is about identity. Who belongs? What binds a people together? The central question is who is “us”?

The distinction matters. A sovereigntist can be culturally liberal, welcoming immigrants yet resisting supranational bodies on grounds of democratic consent. A nationalist may accept supranational institutions if they serve national prestige, in the way that Charles de Gaulle used the European project to elevate France.

In practice, sovereigntists borrow nationalist language, and nationalists cloak themselves in sovereignty. But analytically they are not the same: sovereigntism is a doctrine of control; nationalism a doctrine of belonging. One can exist without the other. Together, they form a potent cocktail now unsettling Western democracies and redrawing the political map.

This distinction explains why the new cleavage has found such fertile ground. Its appeal is neither purely cultural nor purely constitutional but the fusion of both, sharpened by lived experience. And nothing has accelerated that fusion more than globalisation.

Why Globalisation Lost Its Shine

Globalisation was sold as a universal good. Open markets would raise productivity, spread technology, and make everyone richer. For a time, the promise seemed real: cheaper goods, booming trade, and extraordinary growth in the developing world. Billions were lifted from poverty, especially in Asia. But within the West, the gains were brutally uneven.

The American experience is captured in the “China shock.” After Beijing joined the WTO in 2001, imports surged. Labour economists like David Autor have shown that regions most exposed to Chinese competition lost millions of manufacturing jobs, saw wages stagnate, and suffered lasting declines in labour force participation. Enrico Moretti estimated that in the US, each factory job supports around 1.6 local service jobs; when plants closed, whole towns hollowed out. Mortality rose too, driven by suicides, overdoses, and alcoholism. These are the “deaths of despair” that reveal how economic loss has become existential to so many.

Unsurprisingly, the political map has shifted alongside the economic one. Studies show that counties where life expectancy stagnated or declined were disproportionately likely to swing toward Donald Trump in 2016. It is no coincidence that Trump’s running mate, JD Vance, first came to prominence with Hillbilly Elegy, his memoir of precisely these left-behind communities. Vance now argues for a sovereigntist turn in US economic policy - reclaiming industrial capacity, reshoring supply chains, and insulating America from what he and others see as a global system rigged against them. The China shock did not just destroy factories; it upended the political consensus, driving a demand for sovereignty as the only route back to security and dignity.

Britain was not spared. Research by the Centre for Economic Performance found that UK regions most exposed to Chinese imports saw weaker firm growth and sharper economic strain. The macro numbers are stark: in 2000, the UK accounted for about 3% of global manufacturing value added; by 2022, it had fallen below 2%, with its share of global manufacturing employment roughly halved. China, meanwhile, became the world’s workshop. The result was not just factory closures but frayed supply chains, atrophied skills, and weakened industrial communities. Britain retains strengths in high-value niches - aerospace, pharmaceuticals, advanced engineering - but the middle of its manufacturing base has been hollowed out.

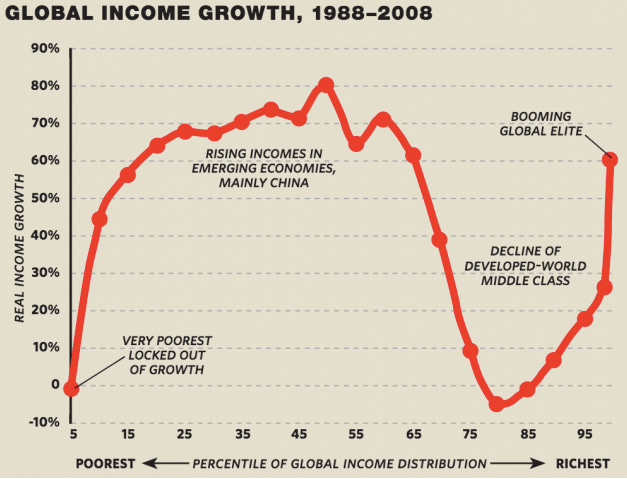

This economic squeeze fed into widening inequality. Branko Milanovic’s famous “elephant curve” shows how between 1988 and 2008 globalisation lifted the world’s poor and enriched the global elite, but left much of the Western middle class stagnant. OECD and IMF data confirm that within-country inequality has increased in most advanced economies from the 1980s onwards; for example, in 2011-12, 17 out of 22 OECD countries recorded higher Gini coefficients (i.e. worse inequality) than in the 1980s.

Source: The American Prospect, using data provided by Branko Milanovic. The so-called “elephant curve” shows that between 1988 and 2008 globalisation delivered large income gains to the world’s poor (especially in Asia) and the global top 1%, but produced stagnation for much of the Western working and middle class - typically located around the 75th–80th percentiles of the global income distribution.

The lesson was clear: globalisation succeeded in aggregate but failed in distribution. It made winners of the world’s poor and the Western elite, but left millions of Western middle-class families behind. That hollowing has become the grievance on which sovereigntism feeds.

Crisis Cascades and the Rise of Sovereigntist Politics

If the China shock and wage stagnation laid the groundwork for sovereigntism, the crises of the past fifteen years hardened it into a political force. Each carried the same

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to States of Play by Sam Olsen to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.