The Great Split: How China and the West Are Reshaping Globalisation

My new co-authored report sets out the strategic implications for businesses and governments of a world dividing into rival economic blocs

Hello and welcome back to States of Play, the newsletter and podcast exploring how the world is changing - from geopolitics to technology, from defence to demographics.

For today’s post I am highlighting my new co-authored paper, The Great Split.

Writing with Stewart Paterson and Derek Leatherdale, we argue that we are living through a seismic shift in the structure of the global economy, one that marks the end of globalisation as we have understood it for the past 30 years.

For more than a generation, companies and governments have assumed that markets would stay open, supply chains would remain interoperable, and that geopolitical tensions could be managed without tearing the world’s economic fabric. That era is now over. The world is reorganising into rival blocs, with countries and companies increasingly forced to take sides between the United States and China.

This is not a theoretical risk. It is already shaping investment flows, regulatory regimes, technology standards and access to key markets. Soon, entire sectors, jurisdictions and even countries will become effectively out of bounds depending on where they sit within this emerging divide. The implications are profound. Supply chains built for a frictionless world will come under intense strain; business models premised on neutrality will become unworkable; and governments unprepared for this structural turn will face severe strategic and economic shocks.

The Great Split sets out why this shift is happening, and what must be done to prepare for the world on the other side.

(If you would like a copy of the Great Split report please click here.)

Many thanks for reading. I’ll be back soon with more insights into the changing world order.

Sam

The Great Split: Why the World is Dividing, and What It Means for Every Global Business

There are moments in history when the tectonic plates of the international order shift in an epoch-defining way. But you don’t always see it happening in real time. Instead, you notice the tremors: the assumptions that no longer hold, the certainties that start to fray, the sense that the world is reorganising its centre of gravity. For the past several weeks, through the Polycrisis 2027 series, I’ve been tracing the converging shocks reshaping global stability: geopolitical rivalry, energy volatility, technology fragmentation, tightening financial conditions. But beneath those surface pressures lies something deeper, quieter, and altogether more structural.

Today, with the publication of my new co-authored report The Great Split: China’s Belt and Road and the Fracturing of Globalisation, I want to examine that underlying fault line. It is a fracture running beneath almost every debate about trade, technology, diplomacy, and security - one that is dividing the world into two competing economic systems. This is not a prediction. It is already visible in the way supply chains are reorganising, in the physical infrastructure being built across Eurasia, in the rival technology ecosystems taking shape, and in the regulatory regimes hardening on both sides of the Pacific.

The Great Split is the story of how three or four decades of globalisation has begun to unspool. It explains why companies may soon find it impossible to operate across both sides of the divide. Why governments are quietly preparing for an era of jurisdictional conflict. And why resilience - the capacity to keep functioning when systems fragment - has become the most important strategic asset of the decade.

A World Dividing Into Two

At the heart of the report is a stark observation: the world economy is bifurcating into two rival operating systems. On one side is the Western bloc, still anchored in the architecture built after 1945. This is characterised by open markets, the dollar as the world’s reserve currency, and the regulatory standards of the OECD world.

On the other sits a rising, increasingly coherent Chinese-led system, built not on openness but on control: state capitalism, industrial coordination, and an expanding web of physical and digital infrastructure.

Globalisation is not collapsing - it is reorganising into rival systems. The Great Split report explains how and why

For much of the post-Cold War era, globalisation rested on a single assumption - that China and the West, for all their differences, would remain deeply interdependent. Western companies would manufacture in China; Chinese firms would access Western capital; both sides would gain from the flows of trade and investment. That assumption is gone. The United States and its allies are now pursuing de-risking and decoupling in key sectors, while China has spent a decade building strategic redundancy: backup systems for shipping, payments, energy, and data.

The result is not a sudden crash, but a slow, decisive divergence: two supply-chain systems; two technology stacks; two financial networks; two sets of rules.

What The Great Split underscores is that this is not “deglobalisation” in the sense of shrinking trade volumes. Instead, it is re-globalisation under rival terms: a world still interconnected, but through competing, and increasingly incompatible, systems. The old logic of interdependence is giving way to a landscape shaped by geopolitical alignment, technological compatibility, and jurisdictional risk.

How the Belt and Road Became China’s Insurance Policy

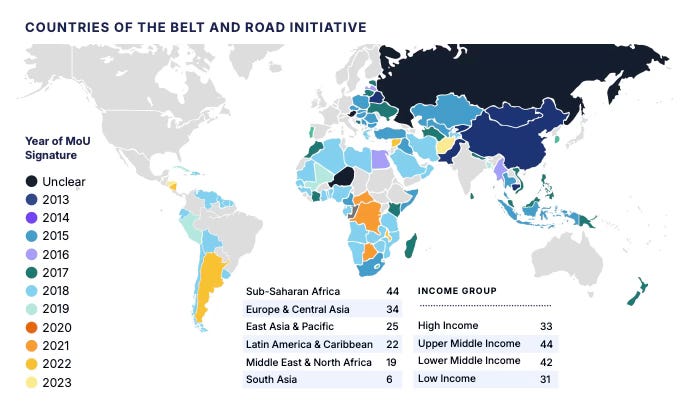

When China launched the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in 2013, many dismissed it as overreach: a grandiose slogan masking patchy, uneven infrastructure projects. That misreading is now untenable. Over the past decade, the BRI has grown into a sprawling ecosystem spanning more than 150 countries, knitted together by railways, ports, power grids, pipelines, digital corridors, special economic zones, and data infrastructure.

What makes this significant is not just the volume of bricks and concrete, but the strategic logic behind it. The BRI gives China:

Alternative routes for goods and energy if maritime arteries are blocked or contested.

A network of dual-use ports, from Piraeus to Gwadar, Djibouti to Port Said - capable of supporting both commerce and naval projection.

A framework for exporting technical standards in telecoms, cloud computing, surveillance systems, and payments infrastructure.

A non-dollar financial circuit, anchored in renminbi clearing and bilateral swap lines with dozens of partner states.

Together, these form a parallel operating system - a world China can rely on even if access to Western routes or financial plumbing becomes restricted. In the report we describe it as Beijing’s insurance policy for a divided world. It reflects a long-standing fear: that China’s access to the Indian Ocean or to dollar-based markets could be choked off during a crisis. The BRI is designed not to replace globalisation but to withstand its fracture.

Europe and the UK at the Fault Line

If the world is splitting into rival blocs, Europe sits directly on the fracture line. For decades, European prosperity rested on a set of favourable conditions: stable maritime routes from the Gulf and Asia; predictable energy flows; deep access to Chinese manufacturing capacity; and a belief that geopolitical tensions could be quarantined from trade.

Those conditions are fading. Geography - long considered background noise - is becoming destiny again.

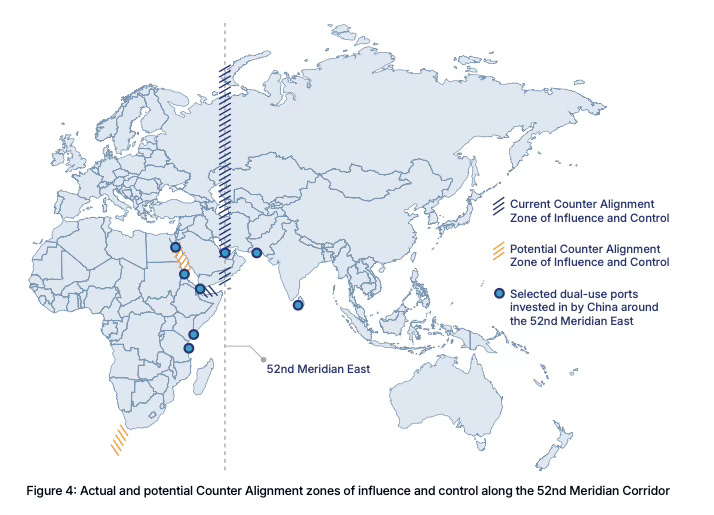

Much of Europe’s commercial bloodstream now flows along what I’ve elsewhere called the 52nd Meridian corridor: a north–south axis running from the Arctic through Russia, Iran and the Red Sea down into the Indian Ocean. Along this corridor, Chinese, Russian and Iranian influence increasingly overlaps at the very chokepoints through which Europe’s trade must pass. It is a route not of European design but of European dependence; and it is becoming more contested each year.

The vulnerabilities are obvious. Europe’s green transition relies on Chinese solar components, battery cells, and rare-earth magnets. Its pharmaceutical industry depends on Chinese precursors. Its logistics network relies on ports and shipping lanes where rival powers are becoming more assertive. And almost all Europe–Asia trade still squeezes through the Suez Canal and the Red Sea. They are maritime arteries that have been repeatedly proven as exposed to pressure, for example the attacks by the Iranian-backed Houthis, and now likely to face sustained geopolitical pressure.

The United Kingdom’s exposure is even more pronounced. London is the world’s second-largest offshore renminbi hub. British banks, insurers and commodity traders sit at the epicentre of global trade finance. Universities and property markets depend on Chinese capital; advanced manufacturing on Chinese inputs. In any sanctions confrontation or maritime crisis, the City of London would be both the executor of Western policy and one of its principal casualties. As one senior financier told us, “When the split comes, we will be the wiring through which the shock travels.”

None of this is alarmism. It is structural reality. The UK’s openness - its greatest advantage in the high era of globalisation - has become a point of fragility in a world increasingly organised around competing economic systems.

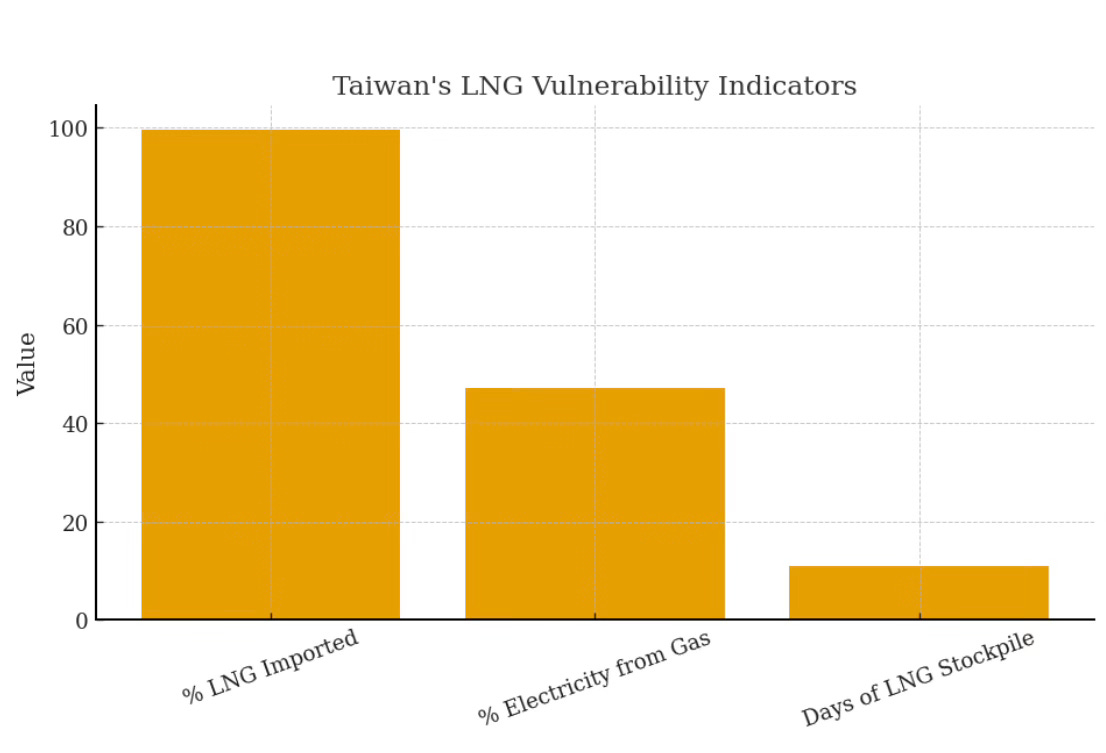

The Taiwan Stress Test

One of the report’s central scenarios considers what would happen if a crisis erupted over Taiwan - whether a blockade, a cyber-siege, or an outright military conflict. The findings are sobering.

A Taiwan crisis would be the most severe economic shock since 1945. Not because of the fighting itself, but because of the cascade of disruptions it would trigger:

Shipping through the South China Sea and Taiwan Strait could collapse overnight.

Insurance costs on rerouted vessels would surge; journey times would double.

Semiconductor flows would choke, stalling global electronics supply chains.

Factories across Europe would run out of components within weeks.

Energy markets would swing wildly; emerging-market currencies would wobble.

Western sanctions and Chinese counter-measures could split the global financial system in two.

And because China now produces roughly one-third of the world’s manufactured goods, the shock would affect every economy simultaneously. It would test not only the resilience of companies but the capacity of governments to manage political, economic, and social fallout.

Crucially, though: a Taiwan crisis would not cause The Great Split. It would confirm it. It would reveal the deep structural divide already embedded in the global system.

Why Businesses Must Pay Attention

This is the point where the analysis moves from geopolitics to strategy - from the broad sweep of great-power competition to the practicalities of the boardroom. For three decades, businesses have assumed that markets were compatible, technologies interoperable, supply chains politically neutral, and regulatory systems slowly converging. Those assumptions no longer hold.

In a divided world:

Supply chains become political terrain.

Data governance becomes ideological.

Technology choices become signals of alignment.

Finance becomes a tool of pressure and coercion.

Jurisdictional risk becomes potentially existential.

A company operating across China, Southeast Asia, the Gulf, Africa, Europe and the United States may soon find itself pulled between incompatible legal regimes. Washington may restrict certain technologies or data flows from crossing the divide. Beijing may respond with export bans, licensing requirements, or counter-sanctions. The result is not simply operational complexity - it is the possibility of legal impossibility.

When the split comes, the City of London, and Europe in general, will be the wiring through which the shock travels

This is why The Great Split matters for every global enterprise. The danger is not choosing the “wrong” side; it is assuming neutrality will remain an option.

Resilience - once relegated to risk committees - is now a strategic function. It means mapping exposure across supply chains, data systems and financial networks; building optionality through diversified suppliers and regional autonomy; and anticipating how export controls and technology fragmentation will reshape competitive dynamics. Above all, it means accepting that geopolitics is no longer an externality. It is the arena in which strategy must now be conceived and executed.

And the same logic applies, with even greater force, to governments.

Why It Also Matters for Governments

For governments, the Great Split is not a distant trend - it is a direct challenge to national security, economic sovereignty, and policy autonomy. The assumptions that underpinned liberal globalisation - that markets would remain open, that technology would diffuse freely, that supply chains would be stable, that finance would remain apolitical - are all eroding.

The report identifies three long-term dilemmas for states.

1. Economic security becomes national security

Governments can no longer assume that critical goods - from semiconductors to medicines, rare-earth minerals to battery components - will arrive predictably from global markets. Supply chain disruptions are no longer exceptional; they are structural. This forces governments to rethink industrial policy, invest in resilience, and reassess dependence on foreign systems that may become leverage in a crisis.

2. Regulatory sovereignty is at risk

As technological and financial ecosystems diverge, governments must decide which standards to adopt. Choices about 5G networks, cloud providers, AI regulation and data flows are no longer technical, but statements of geopolitical alignment.

3. Jurisdictional conflict becomes a defining challenge

Just as companies face contradictory rules, governments face conflicting obligations. The US may demand tighter controls over technology and investment flows; China may impose penalties on countries that comply. Middle powers - from Europe to India to the Gulf - will find themselves navigating a world where legal and technological systems pull in opposite directions. The issue is not merely economic; it is political. A state’s ability to legislate, enforce rules, and retain strategic autonomy may be constrained by the gravitational pull of competing blocs.

In short: The Great Split is not just reordering markets; it is rearranging power.

Why This Matters Now

The Great Split is not a future scenario. It is unfolding now, in the hard infrastructure of the world economy: in ports and pipelines, in data cables and payment systems, in export-control regimes and investment screens. The international order is not collapsing, but reorganising.

The most dangerous assumption any organisation can make is that it can remain “global” in the way it once was. The era of strategic neutrality is ending. The United States and China are setting out incompatible expectations of how companies should behave, what technologies they can deploy, and which jurisdictions they can straddle.

This is why understanding the Great Split is no longer optional. It is the essential context for strategy in the 2020s.

The future will not reward size alone. It will reward resilience. It will reward clarity. It will reward those who recognise early that the fracture is real - and prepare accordingly.

This report is an attempt to lay out that reality with precision and clarity, and to help organisations anticipate what comes next. For governments, businesses, and all of us who depend on a functioning global order, the question is no longer whether the world is splitting.

It is whether we are ready for the world that emerges on the other side.

(If you would like a copy of the Great Split report please click here.)